From the charming and the familiar to the scary and the rare; from the ornamental to an essential resource

all the way through to food, trees are beautiful, inspirational and mysterious, and so vital that without them we simply wouldn’t be here.

By Rachel Love

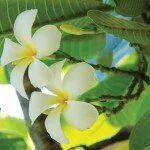

A few years ago I bought a frangipani tree (Plumeria), it was the first mature tree I had ever purchased, and it was literally a groundbreaking experience. Delivered to my house on the back of a truck, it took five men to carry it and replant it in my garden. I was dismayed to watch it go into stress and drop all its leaves, but it continued to flower and within a few weeks it was happily sprouting new leaf buds. Actually it’s difficult to kill a frangipani, they are easy to propagate, and you will find them all over Bali; their sweet-scented flowers are used in every form of decoration, including the spectacular head-dresses of the Balinese Legong dancers. Often associated with ghosts and always found in graveyards, the white frangipani is a symbol of immortality because the tree will continue to blossom even after it has been uprooted.

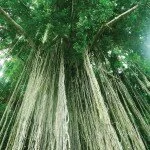

Further ubiquitous symbols of immortality in Bali are the massive banyan trees (Ficus benghalensis) that you will see towering above almost every village temple and cremation ground. Banyan trees are considered the ‘elders’ of the tree kingdom; it is believed that they are inhabited by spirits and demons, so they are accorded special respect. They are preserved and worshipped; the Balinese build shrines at their feet and gird their trunks with the black and white chequered poleng cloth that marks the sacred. You may even notice that motorists will honk their horns in polite greeting, if they pass a banyan tree on the road. The beginnings of these strangler figs are most unusual; the seeds are carried by birds and sometimes dropped on the branches of trees. Nourished by moisture and warmth, the seeds quickly sprout long aerial roots that grow down the trunk or dangle from a branch. Once these grasping roots reach the ground and get a firm grip in the earth, they enlarge to become strong trunks that wrap themselves firmly around the host tree. As the banyan tree matures, new roots grow from all of its branches, pushing into the ground and forming new trunks. The banyan is subsequently known as “the tree that walks” because it moves forward, slowly, with every new trunk that it puts out. It can grow to over 30 metres in height, and displays a majestic and refreshing canopy of green above its trunks.

Another revered tree that was once found in every village, but is now becoming rare, is the ‘majegau’ (Dysoxylum densiflorum), Bali’s floral emblem. Akin to mahogany, and renowned for its strength and beauty, its fragrant wood can only be used in sacred buildings or in the construction of cremation towers. The Balinese regard all living things as manifestations of the Hindu unmoved mover, and trees are no exception. It is considered wrong to cut down a tree without first making offerings and asking its pardon or permission.

The splendour of the breadfruit tree (Artocarpus altilis) stands out in any garden, grove, or yard; its dark-green lobed leaves forming a graceful tapestry. A member of the fig family, it is believed to have originated in Java and grows to over 18 metres, with branches spanning a similar-size diagonally. The inner bark lends itself as a second-grade cloth, the slightly abrasive leaf sheaths are used for polishing utensils, the young buds are a medicine for mouth and throat, the white sticky sap becomes glue, and the spherical fruit a starchy nutrition-packed food.

I am the Lorax, I speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues.”

-Dr. Suess

A particularly fabulous flowering tree that you might identify in hotel gardens or beside the road, especially on the Bukit Peninsula and in West Bali, is the ‘flamboyant tree’ (Delonix regia). This is a good shade tree with an umbrella-shaped crown that blooms in abundance with vivid vermillion, orange, and less commonly yellow, flowers during the rainy season. It is one of several species known as the ‘flame tree’ or ‘flame of the forest’, a moniker that also applies to the stunning ‘African tulip tree’ (Spathodea campanulata), popularly known as the ‘syringe’ or ‘fountain tree’ because its reddish-orange or crimson flower buds are filled with a sweet watery sap that can be squirted out when the tip is snapped off. The ‘rose of India’, meanwhile, boasts showy mauve flowers and a bark that is employed medicinally to combat abdominal pains.

The distinctive pagoda-shaped kapok (Ceiba pentandra) is another familiar sight on the Bukit Peninsula. The fruits are oblong capsules that hang in bunches and are harvested for their silky floss. This soft material is fine, soft, elastic, impervious to water, and much sought after for stuffing pillows and mattresses.

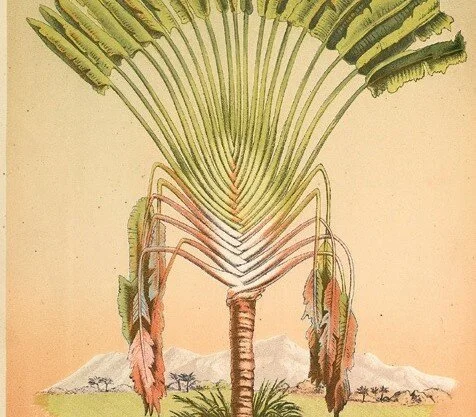

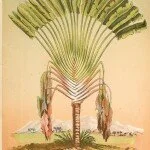

You will see numerous species of palm in Bali, and a particularly eye-catching one is the red ‘lipstick’ or ‘sealing wax’ palm (Cyrtostachys renda) with its bright scarlet leaf axis and sheaf. It requires constant hot weather for the colour to develop, and can be difficult to propagate; because of this and its striking appearance, the palm sometimes sells for prices as high as US$1,000 to collectors and gardeners. The ‘traveller’s palm’ (Ravenala madagascariensis) is also very eye-catching, characterised by a wonderful fan-shaped crown of leaves at the top; it actually belongs to the banana family and not a true palm. The common name comes from the fact that the fan tends to grow on an east-west line, providing a crude compass. Furthermore, there have been tales of thirsty travellers finding relief from the base of the leaves where water accumulates. As much as one-and-a-half litres of water can be obtained from one tree, making it a lifesaver in times of prolonged drought.

If you’re close to the ocean, you may spot a beach hibiscus (Hibiscus tilliaceus); notable for its bright yellow blooms, each with a maroon centre. The flowers drop off in the late afternoon and line the Seminyak beach road. The heart-shaped leaves are a natural remedy for malaria, coughs and bronchitis, while the undersides of the leaves are covered in downy hairs and are used for fermenting soya bean tempe.

The trees seen in the gardens and along the roadsides of Bali, therefore, reflect the long agricultural, cultural and religious traditions of the island. They are grown for food, ritual offerings, medicine, parchment, cushion-stuffing, clothing, utensils and water carriers, while the timber is utilised in furniture-making, carpentry and construction. Indeed, trees in Bali are worshipped and revered as are the gods, and, at their most humble, are always a most highly appreciated source of shade.

“If a tree dies, plant another in its place.”

– Linnaeus