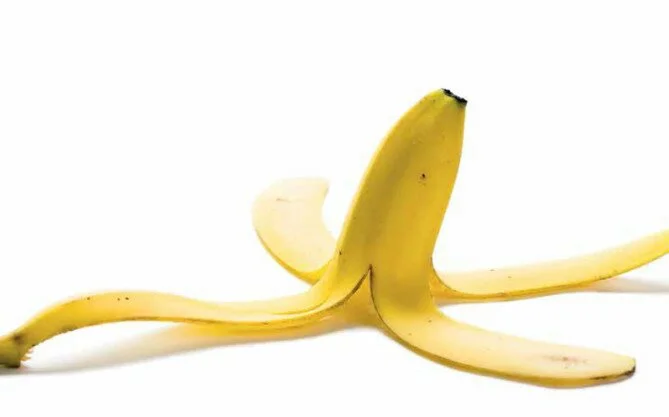

ONCE UPON A TIME, PLASTICS WERE THE SAVIOUR OF HUMANITY’S STORAGE PROBLEMS, WHICH ENABLED OUR CONSUMER NATURE TO KICK INTO TOP GEAR WITH CHEAP AND DURABLE MATERIALS FOR THE MANUFACTURE OF CHEAP-AND-EASY-EVERYTHING TO REPLACE THE CUMBERSOMENESS OF METAL, GLASS AND CARDBOARD. IT SEEMED TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE, AND FOR A WHILE IT WAS, BUT NOW THOSE PLASTIC CHICKENS HAVE COME HOME TO ROOST AND WE ARE DROWNING IN A SEA OF DISCARDED CONSUMERISM, SOMETHING OUR OCEANS ARE TAKING LITERALLY.

Discarded plastics litter the Earth, and a frightening amount ends up in our oceans. A new report from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation of the World Economic Forum paints a dire picture, projecting that there will be one ton of plastic in the ocean for every three tons of fish by 2025, and more plastic by weight than fish by 2050. Last year, researchers estimated there were 5 trillion pieces of plastic in the ocean, many of which are small enough to be ingested by ocean life and work their way through the food chain, ultimately arriving on your plate. Unsurprisingly, toxicologists say this is problematic and potentially harmful to human health. Research has shown that plastic acts like a sponge for other chemical contaminants in the water, and fish that ingest them are more likely to have liver problems and tumours.

If you thought the Great Pacific Garbage Patch—a giant vortex of manmade debris that accumulates and swirls in the middle of the ocean— was frightening, the new report is far more troubling. Currently, at least eight tons of plastic leaks into the ocean every minute, which the report says is equivalent to dumping a garbage truck full of plastic straight into the sea. That will increase to two trucks per minute by 2030, and four per minute by 2050. Annual global plastic production, currently at 311 million tons, is set to explode worldwide, doubling in next 20 years and arriving at 1.12 billion tons by mid-century. And though recycling can help prevent plastic ending up in the ocean, disposable plastic products are still a problem, regardless of whether or not they are broken down and reused.

“Plastics are the workhorse material of the modern economy, with unbeaten properties,” said Dr. Martin R. Stuchtey of the McKinsey Center for Business and Environment, which helped produce the report. “However, they are also the ultimate single-use material. Growing volumes of end-of-use plastics are generating costs and destroying value to the industry.

Currently, 6 per cent of the world’s oil use is devoted to producing plastics—the same amount used by the global aviation sector. That is expected to increase to 20 per cent by 2050. Producing plastic today uses 1 percent of the world’s carbon budget, the amount of energy that can be expended annually in order to keep the world from warming by less than 2 degrees Celsius. Global consensus is that remaining under this level is necessary to prevent catastrophic climate change. Plastic will account for 15 percent of the carbon budget by 2050.

On the bright side, plastic can be recycled for its components, but just 5 per cent of plastics are effectively recycled. Forty per cent go to the landfill, and a third into nature. And the economic case for recycling plastic is getting more tenuous, as it’s cheaper to make plastic from freshly pumped oil than it is to recycle plastic, given the current low price of crude. The report suggests that to turn the tide against a plastic-filled ocean and global disaster scenario would require a major overhaul of our usage. The biggest step would be to change the economics and processes of recycling, improving the collection of plastics by creating incentives to do so and then more efficiently recycling them. New materials should be developed to take the place of plastics, and plastic items need to be better designed to encourage reuse.

But food security may depend on solving these challenges. Not only does plastic threaten seafood as a food source for humans and other predators, the oil used to produce plastic is heating the planet and leading to more difficult farming conditions globally. Breaking our plastic addiction could be important to prevent or slow other tangential threats related to climate change. It won’t be easy—the report itself calls some of the necessary steps “moonshots.” But if we want to be able to consume plastic-free fish, we’ll need some of that much-touted “human ingenuity” to bail us out.