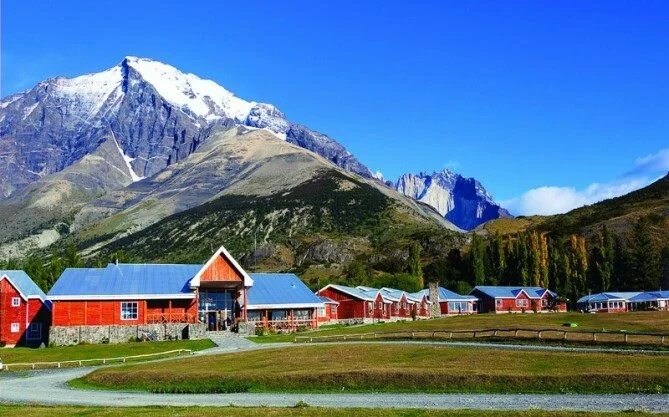

When buying leasehold land in Indonesia as a foreigner the prospect of not being able to renew that lease can be a disincentive to building too permanent a structure. There is, however, a solution in the form of a portable home, which can later be fl at packed and taken away when the lease is up. Whether one is looking for an open sided dining gazebo, a small wooden building to serve as a standalone offi ce or spa pavilion, a self-contained guest room, or a fully-functional house complete with fabulously carved detailing, it’s possible that a ‘joglo’ building – portable or permanent – could be the answer.

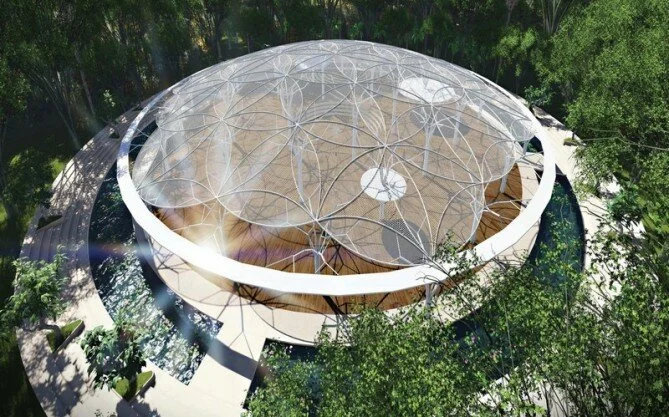

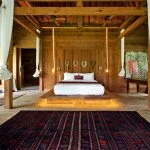

A growing number of locals and foreigners, including French-born, Bali-resident, Alexa Aguila, are buying damaged antique timber houses from Java, and reviving the natural beauty by replacing the missing or decayed wood with recycled wood. Alexa reworks the design and uses the components of more than one old structure to construct each new-yet-historical building, which is then plumbed, wired for electricity and fitted for air-conditioning and all modern conveniences. “Traditional Javanese houses are not practical or comfortable for modern-day living,” explains Alexa. “They are closed-in and dark with tiny windows and little or no ventilation. Light is a modern concept.” At ‘Bali Ethnic Villa,’ Alexa’s three-inone holiday rental property in Umalas, and at her new project in Ubud, Alexa has modifi ed the old structures by installing large glass windows and wide, open-sided verandas. “The structure of a joglo is very special, with a beautiful roof shape, she says. “You can feel the handcrafted energy of the skilled carpenters and carvers, and I love the natural colour of the teakwood – the colour of a lion.”

The traditional 19th century vernacular joglo houses of the Javanese people were wooden frame buildings designed to represent the best of human traits. Originally constructed with precise building standards and specifications, the artisan would fast and meditate before performing specific tasks in the building process. These buildings were crafted from premium teakwood in the historic towns of Kudus and Demak in Central Java – an area where skilled artisans have developed the art of carving wood to the highest degree of refinement – and sophisticatedly constructed using traditional tongue and groove techniques without the application of any metallic nails or bolts. The quality of the wood gave the building a lasting presence. Occasionally, jackfruit ‘nangka’ wood was used, as it was considered to be a special wood with lasting character and great strength.

In the structured Javanese society of the 19th and early 20th centuries, a joglo reflected social status; this type of building was reserved only for palaces, offi cial residences, government estates, and the homes of noblemen. In fact, joglo houses were so highly cherished and highly priced that only wealthy people or noble society could afford to purchase them. A nobleman’s joglo would feature elaborately carved Javanese screen walls and a soaring ceiling displaying layer upon layer of ornate hand-carvings, symbolic of his social status. It would be a place where guests and community could meet.

A traditional joglo consisted of two parts; the pendopo and dalem. The pendopo was the front section of the building – a wide veranda without walls or partitions, featuring a large roofed space supported by columns; this area was used as a reception hall and living space. The dalem was the inner section, the private part of the house, often just one big space or sometimes completed with a wooden screen wall to create a small living area at the front and the main family room behind. Random visitors would be received at the veranda, more important guests would be received in the smaller living room, and good friends or family would use the main room. There were no bathrooms or kitchens inside. Ultimately, the design of the joglo lay in the hands of the owner who would choose carving styles and structural details, along with the quality of the timber. In many cases people would buy the trees while they were still standing, in preparation of building.

Joglos are distinguished by their trapezium shaped roofs, each with a tall and steep central section designed to mimic a mountain. According to Javanese philosophy, to succeed and get the top, you have to start from the bottom. Success is not an overnight thing but a journey through steps and responsible actions. The high part of each roof is supported by four or more main wooden columns called soko guru, completed with the tumpang sari (essential layers) – a series of staggered horizontal beams, usually an uneven number with elaborate carvings – that tie the pillars to one another and support the central portion of the roof. The main entrance doors or gebyok might also be intricately hand-carved, and the sometimes fluted pillars lavishly and exquisitely ornamented with trellis-shaped grooves, perhaps, carved daisy-chains and urns overfl owing with flowers.

Nowadays, traditional joglos in Java are a thing of the past, used as workshops or for housing cows or chickens. Many have been sold for wood to make furniture, but a few still stand in the kampung villages as a reminder of a rich legacy that is slowly fading away.

Rachel Love