Tribal festivals the world over are more often than not about checking the omens to see if the Gods will smile favourably for the coming year of planting, hunting and fishing. Running out of petrol one kilometre short of Bali airport 45 minutes before a 0645 flight to Sumba to experience the Pasola, one of Indonesia’s most colourful, and most dangerous, festivals was definitely not a good omen for me. It’s amazing what hard currency will do for a sleeping taxi driver so early in the morning, however, and when I offered him five times the normal rate to get us to the airport he was all over it, and a potential crisis was averted.

The island of Sumba, formerly known as the Sandalwood Island, is one of the least known – but for some, the most rewarding – of Indonesia‘s islands. It has a rich history and culture and is noted for its horses, sandalwood, impressive megalithic tombs, fine hand-woven ikat cloth, great surf, pristine beaches, and the war ritual ceremony that we had come to see.

The Pasola ritual is part of the island’s worship of Marapu, the ancient animist belief system of Sumba, and it falls on the 19th day of the 10th month of the lunar calendar around February and March, when priests look for signs in the entrails of chickens and buffalo and the nyale sea worm spawn in their millions, signalling the start of Pasola and the time of the horsemen.

Sumbanese men are virtually born on horseback, and they cherish their steeds like members of the family. Although tourism and infrastructure development are slowly creeping in, the men still ride horses rather than drive cars. They are a symbol of high status and are ridden without the benefit of saddles or stirrups, making their riding prowess even greater.

Pasola is a ritual of bloodletting and mock battle on horseback that goes back centuries. It‘s similar in many ways to a medieval joust, and opponents ride out on their horses at high speed to throw spears at each other trying to ‘slay’ their opponent – or at least make a really hard hit to the body.

Two teams of around 50 men from opposing villages gather at either end of an oval arena around one hundred metres across, brandishing blunt, wooden spears and decked out in brightly-coloured sashes and headgear, riding steeds that are equally as colourfully attired. Small squads of riders head out trying to goad the other team so battle can commence. There are many taunts and feints and false starts, but when the teams finally charge and battle commences the crowd goes wild as the spears are hurled and riders duck and weave to dodge the missiles, sometimes dropping right below the horse’s body to avoid a missile, whilst all the time time trying to hit their opponent in return. It‘s all over in a matter of seconds, before they retreat to their respective camps to wait the next charge.

The arena at the village of Kodi, where this day‘s event took place, was a grass field packed with what must have been about 15,000 spectators crowded into any space they could find. Stalls lined the rear perimeter providing snacks and warm beer, and the spectators were standing 20 deep around the edge of the field, with still more packed onto hillsides, some in trees and on the tops of the huge megalithic stone tombs within which lie the bones of their ancestors.

When spear hits flesh or bone the roar from the bloodthirsty crowd is deafening. The ecstatic fans jump up and down screaming and shouting in jubilation, and the successful ‘knight‘ does a victory ride in front of his home supporters to bask in their adulation much like goal scorers at a Premier League football match. It‘s not just the kids who lose control, either. Two old ladies to my left were in raptures, yelling in a warbling scream using their throats, much like Bedouin women of North Africa; a piercing pulsating cry of celebration screamed through red-stained betel nut lips.

In days of old the idea of the joust was to draw blood, and deaths were not uncommon due to the fact that real metal-tipped spears were used. In fact, to kill an opponent was seen as the highlight of the festival, with the requisite blood having been spilled into the earth, thus guaranteeing a good harvest. These days it has been curtailed somewhat by government decree with the introduction of blunted wooden spears to make it a bit more civilised. Deaths and serious accidents do still occur, but it is increasingly rare.

Crowd control is a bit of an issue and even with marshals trying to keep everyone back, the playing area gets smaller and smaller as people push ever closer to the action in their excitement. There are referees and occasionally the game will stop as the crowds are told to step back before the game can continue. It‘s for their own safety, of course, but blood is blood, and the gods needn‘t care where it comes from.

If an errant spear flies off course into the crowd it seems to be just what the throngs are waiting for. When one spear impacted hard into a spectator on the other side of the field I was left standing alone as everyone around me ran off with their phone cameras at the ready to stare and photograph the hapless victim. The jousting stopped for about ten minutes until the crowd was back in their places and the victim was back on her feet. It seems rubbernecking is an international pastime we all share.

Riots are rare but not uncommon, and there is a strong police presence just in case things get out of hand. One story goes that not that many years ago the village elders, upset at the new safety regulations installed by the powers that be to make it more tourist friendly, wanted to sacrifice one of those tourists to appease the gods, and perhaps send a lesson to officialdom. Lucky the boys in khaki with their semi-automatic weapons were there to keep an eye on things and stop an international incident.

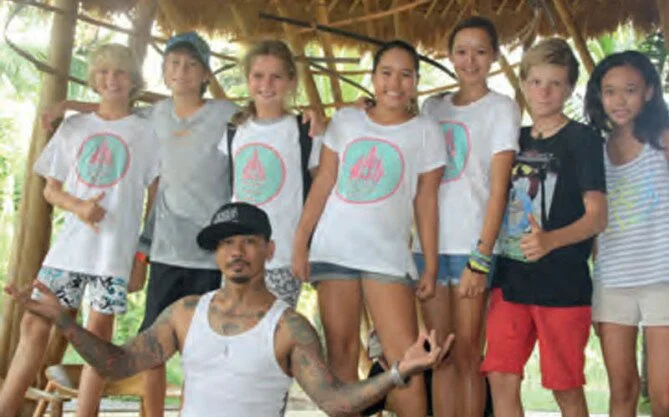

All in all we spent four hours at the festival watching the fighting, meeting locals, taking pictures, and as per usual in the remoter parts of the world, posing for many hand phone photos with excited youngsters wanting to make friends and practice their English. Not many tourists do make the journey to Pasola, (we saw only three others) but for those who do the rewards are beyond belief. For me it was one of the most amazing and exciting cultural events I have ever had the pleasure to witness anywhere in the world.

There are no winners or losers at the Pasola, this is all about their gods and community. When it‘s all over, the crowds disperse back to their villages and thatched roofed houses, and the riders go home to celebrate and talk up their tales of glory into future legend, or to lick their wounds and wait to see if the gods have been pleased in the form of a bountiful harvest.

Thomas Jones

How to Get There.

Garuda and Lion Air fly every day to Tambaloka making a brief stop in Komodo.

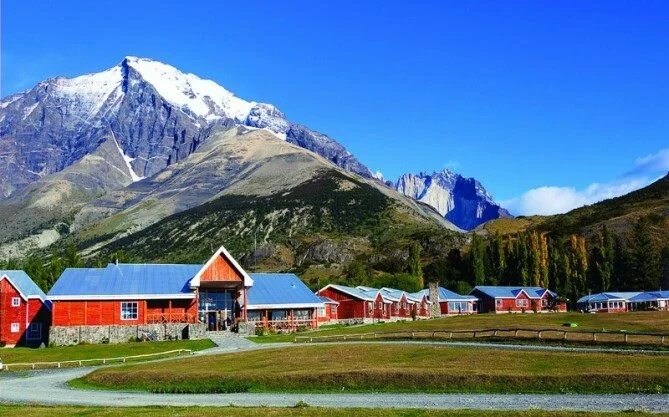

Where to Stay.

The Newa Resort is located 10 minutes drive from Tambaloka and while not the most well-equipped hotel in the world the rooms are large, the beds comfortable and the white sand beach. Ask management for some hammocks for the veranda. As for a guide, ask for Agus.

www.newasumbaresort.com