There has never been anything mild about chillies. A member of the nightshade family and a cousin of the

tomato, potato and eggplant, the chilli is loved and hated for the searing effect it has on our taste buds.

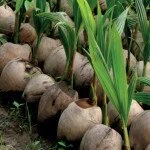

Chillies are native to South America, and there is archaeological evidence that farmers in villages from the Bahamas to Panama to Peru domesticated the spicy fruit – yes, the chilli is most definitely a fruit – more than 6,000 years ago, making it the world’s oldest condiment. In 1492, Christopher Columbus didn‘t just discover the New World while trying to find a short cut to the East Indies; he sampled a plant, mistakenly thought it was a relative of the black pepper, and dubbed it a “chilli pepper.” Diego Álvarez Chanca, a physician on Columbus’ second voyage to the West Indies in 1493, brought the first chillies to Spain, and wrote about their medicinal qualities. The plants were initially grown in the monastery gardens of Spain and Portugal as botanical curiosities, but the monks experimented with their culinary potential and discovered that their pungency offered an inexpensive substitute for black peppercorns, which were so costly that they were used as legal currency in some countries.

The remarkable spread of the chilli (or chili, or chile, or chilli pepper, to use just a few of its myriad names and spellings) is a piquant chapter in the story of globalisation. Few other foods have been taken up by so many people in so many places so quickly. It is believed that the Portuguese cultivated the chilli pepper in their colony of Goa in India, as it features heavily in Goan cuisine. From here, chillies spread throughout India and journeyed through Central Asia and Asia Minor. Meanwhile, Arab and European traders carried chillies via traditional trading routes to China, the East Indies, Korea and Japan, where it was incorporated into the local cuisines.

And what of the actual taste? The feeling is all too familiar; dip into a seemingly innocent tomato sambal, and lmost immediately your tongue willstart to tingle, your cheeks will redden, and beads of sweat will form on your

forehead. The heat is created by a series HOT STUFF There has never been anything mild about chillies.

A member of the nightshade family and a cousin of the tomato, potato and eggplant, the chilli is loved and hated for the searing effect it has on our taste buds. of related hydrophobic (water-hating) compounds known as capsaicinoids, concentrated in the chilli’s internal ribs and seeds, and produced by the plants to deter predation by animals – interestingly, birds are not affected, making chilli a defence against mammals in favour of avian seed propagation.

The chilli burn stems from a chemical reaction that occurs when capsaicin bonds with the pain receptors on the insides of our mouths, which are the same neurons that detect heat. Capsaicin dissolves in fat, oil and strong alcohol but not in water. This is why drinking water is ineffective as a way of eliminating the burning sensation, as it will only spread the capsaicin around the inside of the mouth, where it will come in contact with

more pain receptors and fan the flames. Milk or yogurt is the best remedy.

The pungency of the chilli is the result of both the plant’s genetics and the environment in which it grows. Although plant breeders can adjust the heat by varying water quantities and temperature levels, genetic control is not yet fully understood.

The intensity is measured in Scoville Units – the ratio of sugar water needed to remove all taste to one unit of the active ingredient, capsaicin. The Scoville Organoleptic Test was invented by a pharmacist, Wilbur L. Scoville, in 1912, while working for the Parke Davis Pharmaceutical Company (now a subsidiary of Pfizer). Scoville developed a simple laboratory test in which humansubjects tasted a chilli sample and evaluated how many parts of sugar water it took to neutralise the heat so that its pungency was no longer noticeable. This dilution was called the Scoville Heat Unit. Today, a sophisticated laboratory test is done by high performance liquid chromatography to eliminate inaccuracy.

Officially, the hottest chilli is the Bhut Jolokia of Northeast India, Bangladesh, and Bhutan. Rated at over one million Scoville units, this chilli pepper is a blazing 400 times hotter than Tabasco sauce; its Indian name translates to ‘ghost chilli.’ By way of comparison, a bell pepper is zero, jalapeño 3,000 and Thai chilli 70,000. Incidentally, police pepper spray is five million, which is a good reason to steer clear of trouble.

So why this bsession with heat and pain? Capsaicin promotes an addictive adrenaline rush due to the body’s nervous system releasing endorphins, a type of mild natural opiate, to douse the fire. It‘s that mix of pleasure and pain that makes eating chillies such a sensational experience. Furthermore, hot chilli peppers burn calories by triggering a thermodynamic burn in the body, which speeds up the metabolism. A green chilli pod contains as much vitamin C as six oranges, more vitamin A than tomatoes, and is a significant source of magnesium, iron and thiamine. We still want more and we also seem to want them hotter and in the past few years, chilli lovers in the UK and the US have become obsessed with competitively eating the world’s hottest chillies.

From familiar curved varieties to those that are pea-shaped, heart-shaped, flat, bumpy and nodular – with colours ranging from lime green to rusty red, purple, yellow, black and bright orange – these pungent pods are now the most widely grown spice crop of all, found in endless cuisines and everything else from frozen meals to fiery martinis. The world is getting hotter. R.L