When I was a little girl, my mother used to make this old-fashioned yogurt-like pudding called junket. She would liberally sprinkle the top with ground nutmeg, claiming it was a good remedy for an upset stomach. My mother also used nutmeg whenever she baked apple-pie or potato gratin, and she’d sometimes add it to soups, stews, sauces, and drinks including eggnog. I remember her telling me that wrapped around each nutmeg was another spice – mace, which she would use in biscuits, cakes and breads. With its distinctive, pungent and musty fragrance, and its warm, slightly sweet taste, the nutmeg flavour is almost too powerful for everyday use. Yet Mum maintained it was her favourite spice because of its extraordinary history, assuring me, “It was once more valuable than gold,” and that “it was believed to have been a cure for the bubonic plague.” She also told me that it came from some obscure tropical islands on the other side of the world.

By Rachel Love

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

- All in a Nutshell

Nutmeg is indigenous to the volcanic soils of the Indonesian Banda Islands, and in the 15th and 16th centuries, this aromatic spice spurred world exploration and shaped colonial empires as European traders sold it at up to a 6,000 per cent markup to meet demand for its qualities as both a preservative and a cure against the Great Plague running rife across Europe. People wore bags of the spice around their necks as a protection against the disease, and it’s plausible that it actually repelled the fleas that carried the bacteria.

With a value such as this it’s not surprising that colonial powers vied bitterly for control of the only place on Earth where this spice could be found. In the early 17th century, the Dutch were so ruthless about controlling the nutmeg trade that they massacred most of the native population of the Banda Islands. Land parcels known as ‘perken’ were then handed to Dutch planters – ‘perkeniers’ – to manage, and the nutmegs were coated with lime before export, preventing enterprising farmers from sprouting the seeds. To curb the blackmarket trade, sailors on the nutmeg ships were required to strip naked and be searched before being allowed to disembark at the destination port. At that time, three nutmegs provided sufficient wealth for the purchase of a small tract of land for any crafty sailor who would survive the voyage.

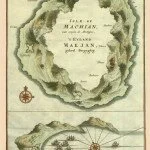

Dutch attempts to maintain a total monopoly on the nutmeg trade were thwarted by the British, who controlled Run, one of the tiny islands in the Banda chain. It turned out, however, that another island, 9,500 miles away, would be the key to securing Dutch control of the nutmeg trade. New Amsterdam was Holland’s strategic colonial outpost in the New World, and in 1667 under the Treaty of Breda, the English traded Run for New Amsterdam, which later became Manhattan.

That deal seems ridiculous to us today, since Manhattan turned into the world’s financial capital, while Run is a rocky backwater covered with nutmeg trees and simple village houses. Nutmeg and mace can be seen drying in the sun outside nearly every home on Run, but the locals no longer get rich from their cherished spice.

Both nutmeg and mace have long been used in medicine. With its strong antibacterial properties; the oil is used to treat toothaches, mouth sores, nausea, gastroenteritis, and chronic diarrhea, and to reduce flatulence, aid digestion and improve appetite. Nutmeg is believed to combat asthma and relax muscles; mace helps prevent insomnia, while an ointment of nutmeg butter, mixed with kenari nut oil, can be applied for the relief of rheumatic pain. In Arab countries, nutmeg is valued as an aphrodisiac; in homoeopathy, it is a remedy for anxiety and depression; and in Chinese medicine, it is used to treat impotence and liver disease.

Furthermore, nutmeg contains eugenol, a compound that may benefi t the heart, while an alkaloid compound known as myristicin has been shown to inhibit an enzyme in the brain that contributes to Alzheimer’s disease and is used to improve memory. Large doses, however, can trigger an acute psychiatric disorder. The myristicin in nutmeg is so intoxicating that it’s actually hallucinogenic – popular in prisons and banned in many prison kitchens. Users may feel the sensation of a blood rush to the head, euphoria and dissociation, which in turn can lead to brutal headaches, convulsions, palpitations, generalised body pain, vomiting, nausea and eventual dehydration, followed by long, deep, almost-coma-like sleep; it can even cause death.

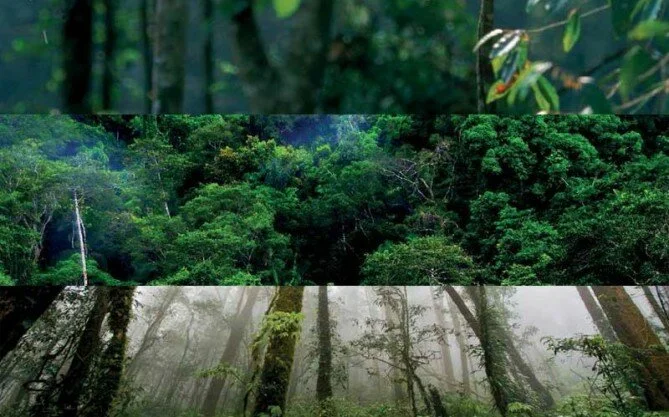

Many decades after watching my mother sprinkle nutmeg on her junket, I came to live in Indonesia and decided to follow the spice trail for myself. My fi rst stop was at Bali’s Sangeh Forest, which is misconceived to be a nutmeg forest. The Dipterocarpus trinervis trees here are a towering 40 metres high and said to be 300 years old. Their local name is palahlar, while the Indonesian word for nutmeg is pala, so the mistaken identity is understandable. I soon realised I would have to travel a fair bit further to find Myristica fragrans – nutmeg trees, which are considerably smaller, averaging 9 – 18 metres in height.

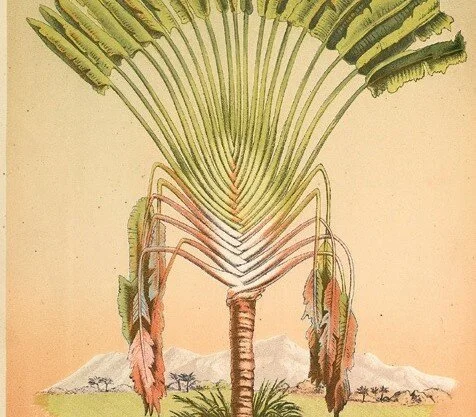

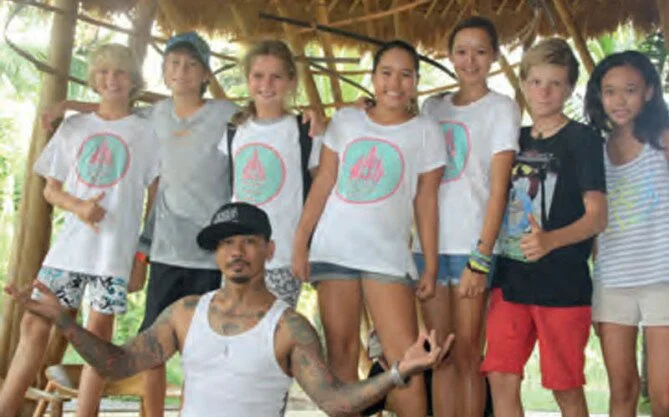

The trail led me east, to Maluku Province, and the fabled Banda Islands, just about as far off the map of the modern world as you can get. Arriving by sea, aboard an old wooden ferry from Ambon, I felt on par with the pioneering adventurers and was awestruck by the plantations. Here, the evergreen nutmeg trees – identifi able by the hundreds of ripening yellow fruits that hang from their branches—grow randomly in the shade of the magnifi cent kenari trees, which themselves yield an almond-like nut locally used in confectionary and sauces. Kenari is what keeps the nutmeg trees growing; towering trees – tall like the buildings in Manhattan, planted to protect the nutmeg from the sun. The fruit is a pendulous drupe, similar in appearance to an apricot. When ripe it splits in two, exposing a crimson-coloured, lacy or fi ligree-like aril – the mace, surrounding a single shiny, brown seed – the nutmeg. The locals use the pulp of the fruit to make syrup, jam and candy; the mace is removed, fl attened out and dried in the sun, and the nut is also sundried for up to two months until the inner nut rattles inside the shell. The shell is then broken to reveal the valuable, edible nutmeat. Secondrate nuts are pressed for the oil, which is used as condiments and carminatives and to scent soaps and perfumes.

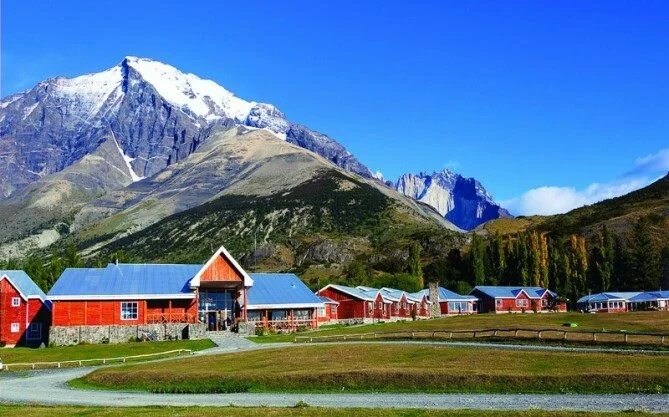

An early European report described the Banda Islands as: “A jewel-like cluster surrounded by crystal waters and brilliant coral reefs, containing hills lined with aromatic spice trees on which perched fl ocks of green and red parrots.” This description can still be applied today. Despite their illustrious history, the Banda Islands are a destination that time seems to have forgotten. These days, intrepid visitors come not to trade for spice – although there is plenty to be found in the market in Banda Neira – but to absorb the historic atmosphere, visit the old forts and the ruins of the perkeniers’ houses, climb the slopes of Gunung Api (fire mountain), dive, snorkel, and marvel at the dolphins that cavort alongside the local boats. That, in a nutshell, is a long way from my mother‘s junket and a far cry from Manhattan!