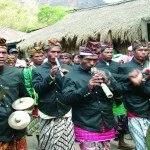

As I scrambled up the steep track, I heard the rhythm of drums, flutes, cymbals and strange percussion. I was surprised; I hadn’t expected to find much activity in this tiny mountain village in Lombok. As I got closer, the music, merriment and laughter became louder and louder. Just what was going on, I was about to discover.

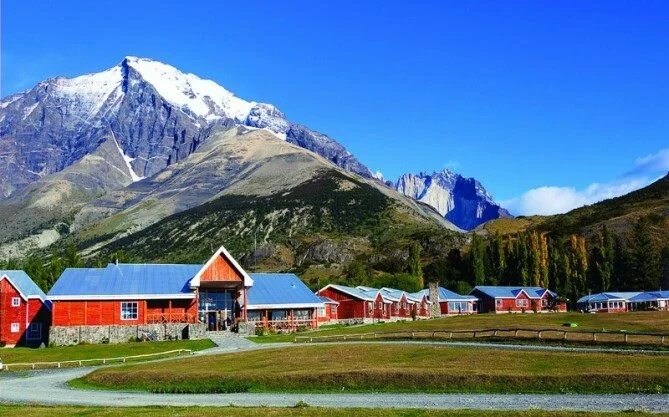

The road from Tandjung to Sembalun Lawang is a journey through time, a harmonious integration of legend, tradition and reverence to God, where shirtless old men still eke out a living from the dry farmland. Bamboo houses hide within coconut groves in the company of graceful cows and floppy-eared goats; scarred dogs patrol the roadside warungs, and dazzling green banana palms with leaves like tattered banners border fields of cassava, corn, garlic, and the red hot chilli peppers from which the island takes its name.

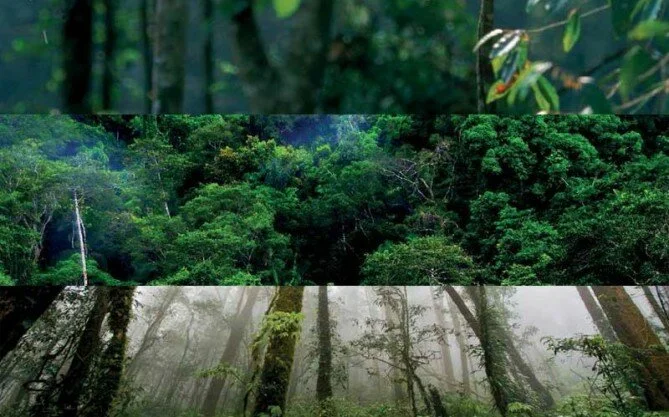

To the west, Gunung Rinjani dominated the skyline and, to the east, grooved angular hills towered in a rimmed semicircle. Rounding the corner into the centre of Lebak Daya hamlet, I gasped with delight. A flamboyant Sasak ceremony of festival proportions was taking place; we’d stumbled upon it by complete chance and I couldn’t believe my luck.

My companions were also thrilled to walk in on the unexpected party, but being residents of Lombok they were much more familiar with such activities. What particularly amazed me was the extent of the pomp and circumstance, the obvious expense; the considerable preparation and creative collaboration that must have taken place in order produce something so magnificent. Yet it was not a public performance; there were no tourists and no television cameras. Indeed, if our little group had not arrived unexpectedly and uninvited, there would not have been any visitors from outside of this remote weaving community.

Immediately in front of my eyes was a sedan chair carried at shoulder height by four polebearers wearing traditional Sasak dress. The wide seat was covered in black velvet, handsomely embroidered in bold colours. Sitting on it were two little boys aged about four and five, together with a slightly older girl with rouged cheeks and bright red lipstick. The boys, both looking rather comical in dark sunglasses, were wearing traditional headdress and sarongs woven with strands of gold. Behind them was another raised chair bearing two more young children; a tiny girl, her head covered by a veil, and a small boy taking the proceedings very seriously in his oversized fake Ray-Bans and ornate black ‘kopiah’ hat.

The chariot was a riot of colour, lavishly embellished with richly dyed fabrics many of which, I later learned, had been handwoven in the village. Even the bamboo poles were wrapped in cloth and each child was tightly gripping a staff, reminiscent of a candy cane, wrapped in ikat with a flag fluttering from the top. A man holding a tall rainbowstriped umbrella sheltered them from the sun. The band struck up again, the children were hoisted high into the air and rocked from side to side as the pole bearers danced. Led by the ‘beleq’ drummers, the ensemble marched through the narrow street, the huge tuned drums, which the players carry across their bodies, functioning as gongs. The music was mesmerising and, encouraged by the villagers’ broad smiles, I was drawn into the procession. Around the next corner I was greeted by another spectacle. Against a startling mountainous backdrop I came face to face with two gaily-painted wooden horses, jingling with tasselled bells and gold coins. Carried aloft, the mounts were flanked by fringed parasols and each conveyed a little boy with an older girl riding pillion.

The occasion was a ‘Nyunatang’ circumcision ceremony for the young boys, with the girls playing the role of ‘guardians’. The ceremony is part of the male Sasak identity practiced both traditionally and within modern society; the cut is performed without anaesthetic, as each boy must be prepared to suffer pain for Allah.

The size of the Nyunatang ceremonies is dependent upon the wealth of the family, and much time is bound up in matters of preparation and finding enough money to collect food and the other paraphernalia necessary to hold an impressive party. In small communities, such as this one, it is customary for several families to pool their resources to create a joint ceremony.

As regular visitors to the area, my companions were warmly welcomed by the head of the village, who eagerly invited us all into his house. With our gatecrasher status suddenly elevated to that of honoured guests, we removed our shoes and sat down on a baize carpet on the floor of his simple home. The women of the household then produced a feast of about seven different dishes. We enthusiastically filled our plates with vegetable and meat curries; a peanut salad; spicy water spinach, and ‘ares’, a dish made from the pith of a banana tree stem, together with red rice and a collection of hot fresh chilli and garlic sambals. The women left us to eat and waited in the adjoining room. Glancing through the curtained doorway, I caught a glimpse of hundreds of bulbs of harvested garlic suspended from the ceiling in neatly-tied bunches.

The meal was completed with fresh bananas and sweet coffee, after which we reluctantly decided that it was time to make a move and leave the villagers to proceed with their ceremony. Outside, the music was still playing, the pole bearers were still dancing and the kiddies were still being paraded up and down the constricted streets. By now, the tiniest boy had fallen asleep; head slumped, sunglasses awry, little legs dangling. It had been a long and tiring day. Rachel Love